Why Bayes? A Decisions First Framework for Business Data Science

Disclaimer

I am speaking on my own behalf and not on behalf of Google or Alphabet.

The Status Quo

The Lure of Incredible Certitude

A common perception among economists who act as consultants is that the public is either unwilling or unable to cope with uncertainty. Hence, they argue that pragmatism dictates provision of point predictions and estimates, even though they may not be credible.

— Charles F. Manski, The Lure of Incredible Certitude (2018)

The Null Hypothesis Ritual

Set up a statistical null hypothesis of “no mean difference” or “zero correlation.” Don’t specify the predictions of your research hypothesis or of any alternative substantive hypotheses.

Use 5% as a convention for rejecting the null. If significant, accept your research hypothesis.

Always perform this procedure.

The ASA Statement

Scientific conclusions and business or policy decisions should not be based only on whether a p-value passes a specific threshold.

— Wasserstein & Lazar, ASA Statement on Statistical Significance and P-Values (2016)

The Problem with P-Values

What p-values DON’T tell us:

- A p-value is not the probability that the null hypothesis (e.g., zero impact) is true

- It doesn’t answer the key business question: “What is the probability our intervention worked?”

- Statistical significance (p < .05) does not equal business or practical significance

- A significant result can still have the wrong magnitude or even the wrong sign

The fundamental confusion:

Correct Interpretation: > Given that the true effect is zero, what’s the probability of seeing our result?

Common Misinterpretation: > Given that we saw our result, what’s the probability that the true effect is zero?

In Praise of Confidence Intervals

Most empirical papers in economics focus on two aspects of their results: whether the estimates are statistically significantly different from zero and the interpretation of the point estimates. This focus obscures important information about the implications of the results for economically interesting hypotheses about values of the parameters other than zero, and in some cases, about the strength of the evidence against values of zero. This limitation can be overcome by reporting confidence intervals for papers’ main estimates and discussing their economic interpretation.

But Confidence Intervals Are Often Misinterpreted Too

✔️ Correct Interpretation

A 95% confidence interval is a range generated by a procedure that, if repeated many times, would contain the true parameter value in 95% of cases.

It’s a statement about the long-run success of the method, not a probability statement about your specific interval.

❌ Common Misinterpretations of Confidence Intervals

The following are all false statements.

The probability that the true mean is greater than 0 is at least 95%. (Endorsed by 38% of researchers)

The probability that the true mean equals 0 is smaller than 5%. (Endorsed by 47% of researchers)

The “null hypothesis” that the true mean equals 0 is likely to be incorrect. (Endorsed by 86% of researchers)

There is a 95% probability that the true mean lies between 0.1 and 0.4. (Endorsed by 59% of researchers)

We can be 95% confident that the true mean lies between 0.1 and 0.4. (Endorsed by 55% of researchers)

If we were to repeat the experiment, 95% of the time the true mean would fall between 0.1 and 0.4. (Endorsed by 58% of researchers)

Why the Ritual Fails for Business

The question business leaders actually need answered:

“How likely is it that Option A is better than Option B?”

This is a question about making a decision under uncertainty.

The traditional frequentist framework wasn’t designed to answer this question directly.

A Decisions First Framework

The Four Steps

Identify Decision(s) – What specific business decision needs to be made?

Craft Business Questions – What questions can inform that decision?

Design, Implement, and Analyze – How do we get reliable answers?

Communicate Findings – How do we present uncertainty clearly?

Business Decisions Are Bets 🎲

- Every decision is a bet on a particular outcome

- Data can help us make smarter bets

- We need to quantify uncertainty to manage risk effectively

- The goal is not to be right every time, but to make better bets

- Quality of information is not binary

- Information to inform bets is not free, sometimes it does not make sense to pay for it

Why Bayes? 🧠

Bayesian statistics is a framework for reallocating credibility among different possibilities as new evidence emerges.

It naturally answers the questions business leaders ask.

Before making a change, we usually consider three possibilities:

- Positive Impact – the change helps

- No Impact – it doesn’t move the needle

- Negative Impact – it makes things worse

Bayes gives us the probability of each scenario.

Crafting a Business Question

A well-structured question can be surprisingly simple, often following the format:

“Does A do B among C compared to D?”

- A: The intervention or action under evaluation (e.g., chatbot, new pricing)

- B: Your clear definition of success (e.g., reduce wait times, increase sales)

- C: The target population (e.g., all customers, a specific segment)

- D: The alternative or baseline for comparison (e.g., no chatbot, current pricing)

Heterogeneity Matters

⚠️ The ATE Trap

Relying only on the Average Treatment Effect (ATE) means you treat all your users as if they are the same.

This can be a costly mistake.

You risk leaving money on the table by missing opportunities to target the right users.

💡 The Solution

To make better decisions, we need to understand heterogeneity.

Methods like Bayesian Causal Forests help us find pockets of opportunity where interventions work best.

Example 1

Example 2

Take Home Message

From: The Null Ritual

- Chasing statistical significance (p < .05)

- Answering irrelevant questions

- Relying on misleading averages and point estimates

- Failing to communicate uncertainty clearly

To: A Decisions-First Framework ✨

- Start with the decision you need to inform

- Estimate the probability of business-relevant outcomes

- Find pockets of opportunity by exploring heterogeneity

- Embrace uncertainty and communicate it clearly to manage risk

The goal is not to be right every time, but to make better bets over the long run.

Questions?

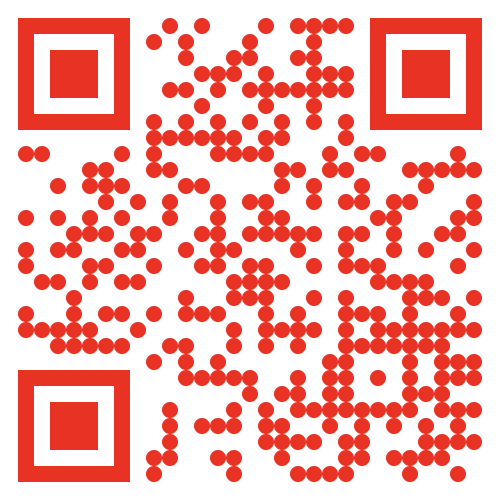

Ignacio Martinez

ignacio.martinez.fyi

Thank you!

Why Bayes? A Decisions First Framework

jsm25.martinez.fyi